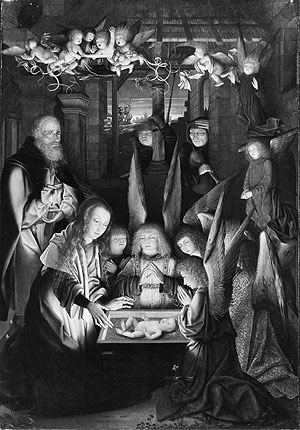

I usually roll my eyes a bit when doctors try to make medical diagnoses of historical figures. However, I found this one interesting: Several years ago two psychiatrists noticed that a 16th century Flemish painting The Adoration of the Christ Child appeared to have one, and maybe two figures with Down syndrome (Report in the British Medical Journal).

I usually roll my eyes a bit when doctors try to make medical diagnoses of historical figures. However, I found this one interesting: Several years ago two psychiatrists noticed that a 16th century Flemish painting The Adoration of the Christ Child appeared to have one, and maybe two figures with Down syndrome (Report in the British Medical Journal).

The Adoration of the Christ Child

16th c. Flemish painting by unknown artist, at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

The angel next to Mary—and possibly the middle shepherd—appears to have facial characteristics typical of Down syndrome: flattened mid-face, epicanthal folds, nose and mouth shape, and short fingers. It could be Europe’s earliest representation of Down syndrome. The authors also make an interesting conjecture about how this may have reflected on society’s view of people with Downs back then:

It is possible that those with milder degrees of mental handicap were not recognised as having what we now call mental retardation; individuals who were perceived as being slightly slow, in contrast to those with severe handicaps, might have been fully integrated into society. In this context, a surviving teen or adult with Down’s syndrome, no life-threatening malformations, and relatively high intellectual function might not have been recognised as sufficiently different to warrant unusual treatment in a social context.

Thus, the individual or individuals in this painting could have been only mildly affected, or mosaic. He or she, or they, could well have been beloved or at least accepted in a family or village group, even a member of the unknown artist’s family.

After all the speculations, we are left with a haunting late-medieval image of a person with apparent Down syndrome with all the accoutrements of divinity. It is impossible to know whether any disability had been recognised or whether it simply was not relevant in that time and place.

(via neatorama.com)